NAVY FIGHTER PILOTS' LINGO

For another thorough resource on this –ahem– important subject,

check out the Tailhook Association's page at:

http://www.tailhook.org.

For general Navy slang enjoy: http://goatlocker.org/resources/nav/navyslang.pdf

| Around "The Boat" | Aircraft and Flying |

| The Pilot And Friends | Index of Terms |

Naval Air types: To suggest additions or revisions to this collection send me a note.

All text on this site © H.Paul Lillebo

|

|

![]()

Around "The Boat":

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

| Abaft | Even farther aft than aft. Behind the boat or whatever. As in, "Honey, is that a police car abaft?" | ||||||||

| Abeam | In Navy talk, adjacent to, not fore or aft, but toward your 9 o'clock or 3 o'clock.. The car that's doorhandle to doorhandle with you on the freeway is abeam. As in, "Damn, honey! That idiot who cut us off is abeam to port. Watch this!" | ||||||||

| ACLS | "All-weather Carrier Landing System." A system that uses automated radio inputs from the ship to control the stick and throttle on an aircraft's final approach to a carrier landing. The pilot could be hands-off all the way to landing, but you bet he keeps his hands on the controls to override them if needed. A pilot had best not use this system all the time, or he'll be rusty at the skill he will need when the system fails: the very tricky job of manually bringing the aircraft aboard the carrier. (Like back when men were men ...) | ||||||||

| Aft | Uh... That's the back end of the boat. Or, adverbially, toward the back of anything. For example, "Sweetheart, has your aft section spread just a bit lately?" | ||||||||

| Air Boss | The Commander in charge of the carrier's flight pattern and flight deck. This is no desk job. During flight operations the Air Boss is located in the tower in the carrier's "island," and runs flight ops in the immediate vicinity of the carrier, where his word is law. Has access to scary loud loudspeakers. He believes – rightly – that humiliation is a great teacher, so as you (the pilot) cross the flight deck after you've landed following some airborne flub, you (and everyone else on the deck) are likely to hear some choice words over said loudspeakers referring to your aviation skills. But to be fair, the Air Boss will just as quickly praise extraordinary professionalism with an "Attaboy". | ||||||||

| Air wing | The aviation squadrons and aircraft aboard a carrier (except for the rescue helos). The air wing is under the command of "CAG" (once "Commander, Air Group" – but now "Commander, Air Wing" but still "CAG") – a senior Commander, and joins the carrier for the duration of a cruise. At the end of the cruise the carrier goes to the yard to be glued back together, while the air wing squadrons may scatter to several airfields. For the next half year or more, the squadrons operate more or less independently, fiddling with paperwork, until the time comes to go to sea again. Then they meet the carrier for another cruise, and become one happy air wing again, under a new CAG. | ||||||||

| Alpha strike | A major, supposedly coordinated, air-to-ground strike, involving much of the air wing (see above), perhaps 50 aircraft or more. Getting all those aircraft "rendezvous'ed" and on their way to the target is always a minor miracle. | ||||||||

| "Anchors Aweigh" | Sure, we love this old Navy ceremonial march, but what's it doing here? First of all, it's the tune every Navy man (and others) hears whenever the ship leaves home port, so it's a part of every cruise. But the real reason: I know you've been wondering forever about why these anchors are going away. Now hear this: they're not going away, they're not going anywhere! It's not "Anchors away", it's Anchors AWEIGH! That is, we're weighing anchor, meaning we're pulling the anchor up. See? You just had a life-changing insight, right? Now, make it stick – hear the tune:

| ||||||||

| Angel | The carrier's rescue helicopter, which hovers off the starboard (that's "right" to landlubbers) side of the ship during all launch and landing (recovery) operations. Every Navy pilot's best friend. Angels is an entirely different word. | ||||||||

| Angled deck | "The Angle" for short. A brilliant WWII era invention, originally British, though it took the U.S. Navy to make it work. Setting the landing area at an angle (10-12°) to the ship's axis allows for low wave-offs and bolters without plowing into aircraft and crew on the forward part of the flight deck, like they used to back in the day... On the other hand, the pilot on final approach has to line up on a centerline that's wandering off to his right. So he has to crab the aircraft all the way to touchdown. That gives you the hazard of right-to-left drift on touchdown, with a very real danger of the aircraft going over the left side of the deck, even if the hook has caught a wire. And then there's the problem of wind. So see that. | ||||||||

| AOOGA | One of the many delightful sounds heard aboard Navy ships, intended to let you know that something's about to happen. If you could only remember what it means! It sounds about like this (click the link in the box):

| ||||||||

| Arrested landing | A successful carrier landing; a "trap". The worst intentional abuse of the body a Navy pilot experiences. Literally a controlled crash into the deck, with shoulder straps jerking you from 150 mph (about 170 mph in the Crusader back when men were men) to zero in about 2 seconds. It's a ride! Special heavy duty landing gear and suspensions distinguish naval aircraft. Here's why: At the moment of touchdown, the vertical speed of the Navy jet is about 13 feet per second. For the pilot it's like being strapped into a chair, lifted 6 feet into the air, and dropped. Tough on the back – my lumbar disks still feel it. A pilot may say, "Whew! Had 5 arrests yesterday." It's an appropriate term. | ||||||||

| Arresting gear | The 4 cables ("wires" to the aviator) stretched across the landing area of the carrier; the aim of the aircraft's tailhook. The ideal pass catches the No.3 wire. If you snag the 1-wire (closest to the ramp) the LSO (Landing Signal Officer) is unhappy. The cables are spooled below deck onto huge hydraulic braking engines, which are adjusted for the weight and speed of each aircraft coming on board. If the setting is too tight, it can rip the tailhook out of the aircraft. If too loose, the cable will play out too far and the aircraft can go over the side or, if it caught the 4-wire, off the end of the angle deck. Often just "gear," as in "Finally caught the gear at bingo fuel." | ||||||||

| Astern | A lot like "abaft". Back there, off the stern. In the picture just below (at "The Ball"), we're located astern the ship. | ||||||||

| Athwart | Or "athwartships." Across the ship, from side to side. Across anything, really, as in: "Wow, honey. Little Billy's foot measures five inches athwart!" | ||||||||

| "Attaboy" | The highest praise from the Air Boss. You've saved an airplane, or performed a minor miracle, or perhaps just looked less hopeless than the day before. The only time the Air Boss uses his loudspeakers without sounding PO'ed. | ||||||||

| The Ball |

| ||||||||

| Ball call | The carrier pilot's radio call to the LSO on final approach, as he rolls into the "groove" and sights the ball. The call includes the aircraft's callsign, type, and fuel state, which the Arresting Gear Officer will use to set the gear's braking power. For example, "Thunder 204, Hornet, Ball, State Three Point Five" – meaning the aircraft's an F/A-18 (a "Hornet") of the squadron using the "Thunder" callsign, with 3,500 pounds of fuel. The LSO may answer "Roger, ball" and Roger Ball has become the prototypical name for a carrier pilot. (I've had feedback that there's actually been a naval aviator with that name in recent decades. That must have been fun.) | ||||||||

| Barricade | A 12-15 foot high contraption of vertical nylon straps that can be raised across the carrier landing area to trap an aircraft with a malfunctioning hook or landing gear. Going into the barricade often results in some minor skin damage. To the aircraft, that is. The pilot will be good as new as soon as the skivvies are laundered. | ||||||||

| Beach | 1. Ashore. "On the beach" means "In town," or anywhere but on the ship. To "hit the beach" is to go ashore. "I'll be on the beach the next two days" (Transl: I'll be riding out a drunk in the squadron's admin). 2. When flying, "Over the beach" means "Over land". Radio report: "Feet dry." | ||||||||

| Bells | The ship's bell has kept time at sea since bells were invented. The bell is struck every half hour and divides the 24-hour day into six 4-hour periods or watches. After midnight, 1 strike of the bell gives 0030; at 0100 two bells are struck, and so forth until 8 bells at 0400. Then the sequence begins again with 1 bell at 0430. Whole hours get an even number of bells, half hours odd. (I'm reminded that onboard ship the Navy thoughtfully avoids broadcasting the bells on the shipboard speaker system between 2200 and 0600.) So when a Navy husband says, "I'll be home at six bells, love," he means he'll be back at 7 p.m. Or eleven. Or 3 a.m. Perhaps this convenient ambiguity explains the origin of the system. | ||||||||

| Below | You can't say "downstairs" on a ship. It's Below, or Down Below. A Navy man would never say "downstairs" at home, either. Like, "Billy, run below and get my hammer." (Of course he would no more say "upstairs": "Billy, if you don't find it below, check topside." And of course there aren't "stairs" onboard ship.) | ||||||||

| Bingo | "Divert to alternate landing field." Verb, noun, adjective, and expletive. In peacetime operations, carriers nearly always have a divert (bingo) field available. An accident can lead to a fouled deck, requiring all airborne A/C to bingo, or a single A/C may have a problem that prevents shipboard landing. The most common reason for bingo'ing is low fuel. At each flight, pilots are briefed on the bingo fuel state: the minimum fuel level with which you can safely reach the bingo field. If you reach bingo fuel and you're still in the air, you'll hear, "Your signal bingo." Sayonara. The Navy spouse needs to know this term, because during the 3rd movement of a Mahler symphony, the aviator hubby will almost certainly say, "Let's bingo." | ||||||||

| Black-ass | Darker than just black. There is nothing blacker than a moonless, overcast, black-ass night in the middle of the ocean. That's when CAG doesn't fly. It's not the flying. It's bringing it back aboard! Nothing raises the pulse rate and pucker factor more than a carrier landing on a black-ass night. That's true. It's been measured. (The pulse rate, not the pucker factor – the world waits for a device to measure the latter.) Scarier than combat! | ||||||||

| The Boat | A blackshoe sailor never calls a ship a "boat". An aviator never calls it anything else. To him, everything that floats is a boat. But the carrier is "The Boat". | ||||||||

| Boat officer | One of the 4-hour watches a junior aviator may be assigned aboard the carrier. An in-port watch: you're officer-in-charge of a liberty boat taking sailors ashore and back. Can be OK in daylight and good weather; you actually get to know some of the sailors. Can also be hell on a midnight return trip with 5-foot swells and 30 drunken sailors onboard. (Do see the "Liberty boat" link.) | ||||||||

| Bolter | An intended arrested landing where the hook fails to engage a wire, so the pilot has to go around for another attempt. There can be several reasons for this, but the most common is simply being high (not like on drugs!) on the glideslope and missing the 4-wire. Other reasons can be hook-skip (more often an excuse) or a damaged hook. A habit of frequent bolters is bothersome, because each bolter stretches out the carrier's recovery time and upsets the Cyclic Ops timing. Nobody wants to be the squadron Bolter King. | ||||||||

| Bulkhead | There aren't "walls" aboard a Navy ship. They may look like walls but they're bulkheads. If you're married to a Navy man, you've probably heard, "Where on this bulkhead should we hang this picture, honey?" And you learn to live with it. | ||||||||

| Burble | An area of air turbulence in the final approach groove right behind the carrier, caused by the island structure, particularly when the ship makes its own wind. You need to be prepared to add power when going through the burble; it acts like the proverbial "air pocket." (When there's enough natural wind that the relative wind comes down the angle deck, the burble will be away from the groove, to starboard, and is no problem. That is, there's only the normal turbulence caused by a giant floating building in a strong wind.) | ||||||||

| CAG | "Commander, Air Group." The Commander of the Air Wing (earlier "Air Group"), i.e., all the aviation squadrons aboard the carrier. Now officially "CAW," but nobody says that. CAG (rhymes with "rag") is a senior Commander who has previously served as skipper of an operational squadron. It may be a while since he has done much flying, and he doesn't really care for night flights, but the job is necessary if he hopes to make Captain and get selected to command an aircraft carrier. CAG flies aircraft from all or several of his squadrons, and his name adorns each squadron's endearingly yclept "Doublenuts" bird. | ||||||||

| CarQuals (CQ) | (Pronounced "care-quals" or "C-Q"): Carrier Qualifications; really a shore-based activity. For a Navy pilot, sea tours alternate with shore duty. After a tour ashore, the pilot has to carrier re-qualify by spending time practicing MLP's at an airfield and performing a number of arrested landings on a near-shore carrier, before going to sea. CQ is often referred to as "hitting the boat," and it does matter where you hit it. (Initial carquals is one of the scariest moments in a student pilot's training. If you make it past this, you'll probably make it to the fleet. Worst is Night CQ. A young pilot's first acquaintance with this frightening experience typically results in a heart rate off the charts.) | ||||||||

| Carrier | This shouldn't even need an entry; a "carrier" is of course an "aircraft carrier," a capital ship. But while we're here ... American carriers have traditionally been named for 1. Politicians, 2. Battles, or 3. Inspirational/memorial/patriotic buzzwords. I include some nicknames (some of them slightly ironic) and radio callsigns of some of the ships, as recently reported by aviators who flew from them. (Duplicate ship names are not uncommon, as a later ship memorializes an earlier, often one lost in battle. And why multiple callsigns? During war time, "callsigns were shifted around to confuse the enemy" – aviation author Barrett Tillman): Politicians. These days new carriers are all named after politicians, including some congressional military budget committee chairmen – but of course this is not for the purpose of flattering or securing funding: USS Randolph, CV-15, Callsign: "Johnstown"Battles This has been out of fashion for at least 60 years; why waste a good opportunity to grease the political wheels?: Yorktown, CV-10, Callsign: "Cactus" & "Steamboat" & "Ocean Wave"Inspirational/memorial/patriotic, etc. This isn't fashionable anymore either; perhaps for the same reason: Wasp, CV-7Carriers are designated by the letters "CV" (V for fixed-wing), e.g., CV-8, the original "Hornet." The letter "N" is added to the carrier's designation to indicate nuclear power, e.g., USS Enterprise (CVN-65) – the first nuclear carrier (which will finally be relieved by USS Ford (CVN-78) after 50 years (!) of service in 2015. A further refinement was the letter "A" for Attack (meaning fighter and attack type aircraft), or "S" for anti-submarine warfare. USS Shangri-La is an example of many carriers, particularly of 1940s and 50's vintage, whose designation and role changed, from CVA-38 in earlier days to CVS-38 in later years, when the demands of late generation fighters and attack A/C outstripped the ship's ability to accommodate them. In the 1970's the designations of Attack carriers were changed to indicate a multi-mission capability, and CVA's became simply CV's again. | ||||||||

| Catapult or "Cat" |

| ||||||||

| Catapult officer | A brave man. One of many on the flight deck. The cat officer stands on the flight deck between the catapults during launch, and gives the signal to fire the catapult after ensuring readiness of the pilot, the A/C, the bow, and the deck. He uses flamboyant signals, to be unambiguous. When the pilot is ready to launch he salutes the cat officer, who returns the salute. Quickly checking the cat track, the movement of the bow, and whatever else is on his list, the cat officer then touches the deck with his hand, usually with a flourish, followed by pointing down the cat track toward the bow, which finally constitutes the signal for the operator to fire the catapult. (The test of the cat officer's nerve comes when a pilot needs to abort the launch – yes, before the cat shot, of course. The pilot signals the cat officer with a shake of the head; the cat officer signals this to the cat operator by crossed forearms. He then signals to release tension on the cat, and steps in front of the wing of the aircraft. This A/C is still at full power, perhaps in afterburner. This takes nads. Only after the cat officer is in front of the wing does he signal to the pilot to reduce power.) | ||||||||

| Centurion | An aviator who has made 100 landings on a given carrier. Even if you're a nugget, when you get your 100th trap you're given a tiny bit of respect. And then there are double, triple, and quadruple centurions. The respect increment falls off; much more than 300 traps on a given boat and it goes negative. They start to wonder why you're stuck on this ship. | ||||||||

| Chopper | Any helicopter. | ||||||||

| Clara | Simply means:"Can't see the ball." When a pilot rolls into the groove, the LSO expects a ball call within a couple of seconds. If he doesn't get it, we hear on the radio: LSO: "In the groove; call the ball." Pilot: "Clara." This usually happens on a straight-in instrument approach, at night or in the soup, where the pilot has to transition from flying on instruments to looking out of the cockpit for the ball for the final 30 seconds or so of the approach. It's a tricky transition. | ||||||||

| Clear deck | The opposite of "fouled deck". It means the carrier's flight deck is ready to receive the next aircraft. The previous a/c has cleared the landing area, and a green light is shown to the LSO. In "cyclic" landing operations the "clear deck" light may come just seconds before the next landing. | ||||||||

| Clearing turn | When launched off the carrier's bow catapults, the pilot makes a quick jog to port or starboard, depending on which catapult he is launched from. The idea is that if the aircraft experiences a problem requiring it to ditch, it won't get run over by the ship. Clearing turns were evidently thought up by the brass, since they make little sense: If an aircraft is in danger of going in the drink, executing a turn loses lift and will exacerbate its condition and make it more likely it'll ditch. No way is a pilot in extremis to stay airborne going to do a clearing turn. Let the Captain turn the ship! As a result, clearing turns are made by all the aircraft that are not in any danger of going in the drink. It's a nice custom anyway. Sort of a polite wave back at the Captain. | ||||||||

| COD | "Carrier Onboard Delivery," pronounced like the fish. [Yes, yes, I know there's no fish called "Carrieronboarddelivery." Don't write me about it.] The transport airplane that ferries mail and VIP visitors between the carrier and terra firma, evacuates medical cases and performs "other duties as required." For decades the COD was synonymous with the S-2F aircraft – the "Stoof" – a 2-engine prop A/C and one of the ugliest A/C anywhere. But it had the Volkswagen kind of ugliness: you could love it for it. (Many old Navy Stoofs are now distinguishing themselves as forest fire tankers.) Lately, the 2-engine jet S-3 Viking has taken over the COD tasks. Faster, better looking than the Stoof, but with a lot less soul. (And no sooner said than gone. The S-3 was retired from the Navy in January 2009.) | ||||||||

| Cold cat | A catapult shot that gives the aircraft less than flying speed. The aircraft, of course, goes in the drink. While always rare, they're a lot more rare now than they were in the days of the hydraulic cats. Reasons for cold cats have included flawed holdback fittings which broke before full power developed in the cat stroke, wrong weight settings, and failures in the catapult mechanism. | ||||||||

| Cut pass | Tsk, tsk. You're in the Ready Room after making a suspicious landing. Unfortunately the rules require that you remain in the Ready Room until the LSO comes by to verbally and publicly proclaim the landing grades. You got a No.1-wire, with a red ball in close. In other words, you were LOW, you almost hit the ramp, you endangered several million bucks worth of Navy property. (That includes the pilot.) LSO comes: Your grade: "CUT." Worst landing grade. Publicly shamed. Scarlet letter. A few more of those and you'll get remedial training. (Shipboard is a lot like prison: Little rewards and punishments make all the difference.) [For those who want the gory details, the LSO's note pad may look like this: CUT. HIG, TMRDIC, NEPAR PNU T1W; meaning High in the groove, Too much rate of descent in close, Not enough power at the ramp, Pulled up nose & taxied to the 1 wire. This, by the way, was exactly how a retired LSO recently described the Korean Boeing 777's crash-landing at San Francisco International, but with "RS" (ramp strike) replacing the last comment.] See LSO code for more on the LSO's mysterious abbreviations, see also "OK." | ||||||||

| Cyclic Ops | Cyclic Operations: The dance of the carrier task force. Let's say the carrier wants to stay in roughly the same area during flight ops, which may last all day. Here's roughly how it works: The carrier must steam into the wind to launch & recover aircraft. This may take, say, 45 minutes. The ship then turns 180° and steams downwind for roughly the same period of time, until it's time to recover the previous launch. Then the carrier turns into the wind again, in approximately the same place where it was located an hour and a half ago. Launch & recover aircraft. Repeat. Repeat again, all day. | ||||||||

| Davy Jones' Locker | The depths of the seven seas, as in a grave. Honored final resting place of tens of thousands of ships and hundreds of thousands of seafarers. (The origin of Davy Jones and his locker is lost, as I understand it, but the legend has persisted for centuries. It was described by Tobias Smollett in "The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle," 1751: "...according to the mythology of sailors, the fiend that presides over all the evil spirits of the deep, and is often seen in various shapes, perching among the rigging on the eve of hurricanes, ship-wrecks, and other disasters to which sea-faring life is exposed, warning ... of death and woe." And Mr.Jones' appearance? "I'll be damned if it was not Davy Jones himself. I know him by his saucer eyes, his three rows of teeth, his tail, and the blue smoke that came out of his nostrils.") Just trying to help, in case you should happen to meet... | ||||||||

| Deck | 1. Of course it means what we expect it to mean: A "floor" on a ship. On the carrier the Hangar Deck is deck "1", with the lower decks numbered downward from the hangar deck: The deck just below the hangar deck is deck "2", etc. Decks above the hangar deck are numbered upward, preceded by the letter "O" (as in "Over"). The Flight deck is normally "O-3" – the third deck up from the hangar deck. And not just on a ship: If you grew up in a Navy family, how many times did your dad say, "Quit whimpering and get up off the deck!" 2. When you're flying, "The Deck" usually means the ground, as in: "After the GIB barfed during the zero G maneuver, I was glad to get back on the deck and get hosed off." On ACM (dogfighting) training hops squadron policy may require pilots to observe a "deck" at 10,000 feet. The idea is to pretend that 10K is the ground, so if you dip below it you've crashed and lost the fight. Of course no one ever admits to busting "the deck," but (shh ... don't tell) you do what you have to do to win. | ||||||||

| Deep-six | At sea, whatever gets "deep-six'ed" is on its way to the bottom of the ocean. Like: "Pay me the $5 you owe me or I'll deep-six your girlie mag." Seafarin' folk use the phrase ashore as well, meaning to get rid of something for good. The "deep-six" phrase apparently derives from the depth reading of 6 fathoms (36 feet), specified as the minimum depth for burial at sea by naval law. (Thanks to Tom Larsson for correcting errors in this.) | ||||||||

| Dip | There are dips and there are dips. The dip in question is a common but completely unauthorized maneuver by a pilot on final approach to the carrier. Just about when passing over the ramp, the pilot, if he's high on the glideslope, may make a quick coordinated move with stick and throttle: Slightly relax back pressure on the stick, while easing off the throttle. Then reestablish. Takes about 1/5 of a second, and drops you perhaps a foot on the glide slope. If you're quick enough the LSO may not notice, but he probably will, and you'll get chewed out for it. C'est la guerre. (Sometimes known as a CAG-dip, 'cause CAG is usually a master at it.) | ||||||||

| Dog | Most hatches on the carrier can be secured against flooding or fire with a system of pivoting steel levers ("dogs"), either on the edges of the hatch or on the surrounding bulkhead. When a lever is moved, the short end of the lever is wedged against the opposing surface, securing the hatch. Dog is also a verb; you dog the hatch. ("Dog" was also, back in the day, radio spelling code for the letter "D," and held all the meanings now found under "Delta", so see that.) | ||||||||

| The Drink | The Sea. Going into the drink is not a good thing. Not in an airplane. | ||||||||

| Engagement | Has nothing to do with prospective marriage. In pilot lingo, this has a couple of different meanings: 1. The tailhook catching a wire on a carrier landing. A good engagement is a trap. You've engaged the arresting gear. An inflight engagement makes for a really bad day. 2. In tactics, an engagement means "engaging the enemy aircraft," e.g., a "dogfight." Used both in real battles and in training flights. A "Hassle." | ||||||||

| Expansion joint | This Dante'esque invention deserves to be better known. An aircraft carrier is made to bend in the pitch axis in a couple of places along its hull. This is accomplished by building in "expansion joints," transverse spaces running the width of the hull, one fore and one aft, nominally about 3 feet in width, that have overlapping side plates, allowing the spaces to contract and the hull to "bend" in heavy seas. No one would care about this except that these expansion joints are also passageways. (That's Navy for "corridors.") More particularly, they're passageways that have led to my stateroom! (Keep calm, Paul.) So you innocently step out of your stateroom in heavy seas, into the passageway, because you've been ordered to make a flight to defend the country, when without warning the bulkheads ("walls" to you landlubbers) of the passageway squeeze inward and threaten to impact your body with some 200 thousand gross tons of force, and you're hoping the engineers have correctly figured that it won't quite squeeze your head to the size of a turnip. Keep calm, you say?? | ||||||||

| Fantail | The back end of the 'boat'. The stern. I know where it's at. Somebody else knows why it's called a "fantail." (Isn't that a kind of pigeon?) | ||||||||

| Final checker | A good idea in every quality assurance program, this individual gives the final OK on a finished maintenance job. He brings responsible good sense and overview to a job that up until then has perhaps been handled by specialists, each of whom has approved their own job. On the flight deck, the F.C. gets "thumbs-up" from the small army of specialists scurrying under and around the aircraft as it is on the catapult awaiting launch: One hooks up the catapult holdback and checks the alignment of the A/C on the cat, others pull ordnance safety pins and show them to the F.C., one checks for leaks under the A/C, etc. The F.C. checks the overall condition of the A/C (tires, gear struts, canopy, wing flaps or position, fire ?!, etc.). The F.C., identified by his white shirt or jacket, then gives the final thumbs up to the catapult officer. All this happens in less than ten seconds. The F.C. is usually a Chief Petty Officer or a Maintenance First Class P.O. | ||||||||

| Fire | Nothing gets your attention aboard the carrier like the rapidly repeated bell over the loudspeakers, followed by "Fire, fire, there's a fire in space ...." Fortunately, the ship's emergency procedures are usually equal to the situation, and the small fire is put out. (Let's not talk about the BIG fires, the ones we all worry about. The ones on the Forrestal and Oriskany, that took hundreds of lives.) We may even get a little blasé about fire calls onboard. No matter, as long as you're on the carrier, with its constant fueling and ordnance-handling operations, fire will be your chief nightmare. | ||||||||

| Flat-top | An aircraft carrier. | ||||||||

| Flight deck | The business district of the carrier, about 60-70 feet above the sea surface. Includes the angle deck landing area and the forward catapult take-off area. The 70-some A/C of the carrier's air wing are parked aft on the deck in preparation for take-off on the catapults. During the landing phase, A/C are taxied forward after landing and parked on the bow end, leaving the landing area free. Huge elevators carry A/C to the Flight deck from the Hangar deck, where maintenance is performed. No film representation can do justice to the deafening sound level, the constantly hazardous interaction of men and machines, and the precise application of immense power that is Flight deck operations. There is nothing else on land or sea remotely like it. The flight deck is coated with a "non-skid" substance, which is slightly tacky when dry, and which when sprayed with salt water, jet fuel, and oil – as it almost always is – becomes the slipperiest surface known to man. When the ship heels, heaves, yaws, and pitches, which it does in spite of stabilization, aircraft on the deck want to move in undesirable directions. And they have. (For this reason, all aircraft aboard ship are tied down with chains at all times when not being moved.) | ||||||||

| Float check | Used to be, ship captains threw all garbage overboard. From the air you could follow the shipping lanes like a road of floating trash. USN has more or less cleaned up its act when it comes to jetsam (jettisoned floatables). But stuff that sinks, that's another matter. So how do you know? You give the stuff a float check. Got a pile of old unusable bolts? The chief's pretty sure they won't float, but he tells the seaman to "float check these". Into the briny deep they go. (Thanks to Naval Flight Officer extraordinaire Hank "Geek" Tingler for suggesting the entry.) | ||||||||

| Fore | Forward or front. Used mainly in phrases like fore & aft, viz. "Fore-and-aft cap." | ||||||||

| Fouled deck | The carrier's landing area is "fouled" when it is not ready to land aircraft. During landing ("recovery") operations, aircraft may come aboard with less than 30 seconds interval. During that time the previous aircraft must clear the landing area. Until it has cleared, the deck is fouled, and a red light indicates this to the LSO. If the deck is not "clear" before the incoming a/c reaches a critical decision point (just a few seconds from the ramp), the LSO will wave off the a/c in the groove. | ||||||||

| Fox Corpen | The carrier's heading for flight operations. Normally, if there's natural wind, there's only one ideal heading for launch: straight into the wind. For recovery the ship would turn slightly to starboard to get the wind down the angle deck. (Hearsay: "Corpen" indicates course, while "Fox" stands for the "F" in "Flight ops." Analogously, "Romeo Corpen" means the course steered during an "Unrep"–Underway Replenishment–operation.) | ||||||||

| Fresnel lens | An ingenious arrangement of prismatic lenses, invented by the Frenchman Augustin Fresnel (pronounced frenél) early in the 19th century. After decades of use in lighthouses, the technology became standard for U.S. carrier OLS only in the 1960's. Provides a more powerful, narrower beam than the traditional mirror, and is more readily stabilized. If technically interested, check this site: http://www.lanternroom.com/misc/freslens.htm | ||||||||

| Galley | The word "kitchen" doesn't exist in the Navy. It's a 'galley.' Naturally, to a career Navy man the room in his house with the stove and fridge is also a galley. | ||||||||

| General Quarters | "Boing, boing boing" reverberates throughout the ship, followed by: "General Quarters, General Quarters, all hands man your battle stations. This is not a drill." G.Q. is the ship's battle readiness and emergency condition. The ship goes to G.Q. when there is serious danger of battle damage, from within or without. At G.Q. each sailor and officer has an assigned station. Pilots muster in the squadron's ready room. | ||||||||

| GQ | General Quarters, as above. Used colloquially to indicate an overreaction: "She went to GQ when I told her I had donated her ugly red shoes." | ||||||||

| Groove | The aircraft's final, visual approach to the ship, when the pilot picks up the "ball" on the ship's OLS. The pilot makes his ball call, adjusts the angle of attack, and concentrates on the ball, controlling speed with the stick and rate of descent with the throttle, unless using autothrottle, in which case it's backwards, or ACLS, in which case he "monitors" with hands on. In the groove the (perfect) pilot does not look at the deck, except for quick scans for line-up, but "flies the ball" all the way to touchdown. | ||||||||

| Hangar deck | The carrier's vast cavern of a deck, enclosed and running nearly the length of the ship a couple of decks below the Flight deck, where aircraft are brought for maintenance, or tucked away in bad weather or when the Flight deck needs to be clear for any reason. The Hangar deck has space for all the carrier's aircraft. The Hangar deck is labeled the #1 deck of the ship; lower decks are numbered 2,3, etc. downward, while decks above the Hangar deck are numbered O-1, O-2, etc, upward. (The Flight deck is typically deck O-3.) Each squadron has its assigned areas on the Hangar deck. Almost any level of maintenance short of a total rebuild can be done here. Three huge A/C elevators allow movement of aircraft between the Hangar deck and the Flight deck. For curious etymological note, see "Hangar". | ||||||||

| Hatch | There aren't "doors" onboard a Navy ship. Even if it looks like a door, it's a "hatch." Most hatches have a method of watertight closure by, say, four to eight dogs around the perimeter of the hatch. The high-speed type is tightened (or "dogged") quickly with a turn of a wheel centered on the hatch, which wedges the dogs against the surrounding bulkhead. An old-salt sailor will naturally call a door in his house a hatch. | ||||||||

| Head | It's said that "a dear child has many names." If so, this spot must be dear indeed. Known to landlubbers by such names as John, comfort station, commode, throne, rest room, wash room, W.C., closet, toilet, crapper, and various less gentile appellations, onboard ship there's one and only one term for the little room in question: The Head. The name is said to have originated on ancient square-rigged sailing vessels, where the sailors relieved themselves at what was then called the head of the ship: the bow, off the bowsprit. Now this may sound crazy. My blessed grandmother always told me, "Never piss off the bow!" and I've found that to be reliable advice. So what were these square-rigged sailors doing? Well, the answer lies in the relative wind. My granny was used to motorboats, where the wind usually comes over the bow. If you relieve yourself over the bow on a motor ship you may get a face-full of it. On a sailing ship, on the other hand, the wind normally comes from behind or off a rear quarter, so the bow is the perfect place to let go a stream, which is gracefully carried off in a forward direction. [An alternate etymology has been suggested (but only by me, here and now, as far as I know): Doesn't common sense, not to mention common experience, suggest that the term reflects the key decisions, the profound plans, the inspired stratagems, that have a way of clarifying themselves at that special moment in this special space?] In any case, it goes without saying that–be it thirty years after a Navy career–whether in a California split level or a classic Cape Cod, this special place will always be "the Head" to a Navy man. | ||||||||

| Helo | Helicopter. Around the carrier, "The Helo" is the rescue helicopter (angel), always airborne during flight ops. | ||||||||

| Hit the boat | A usual phrase for doing carrier qualifications ("carquals"), which see for more. | ||||||||

| Holdback | The lowly holdback fitting stands (or hangs) between the pilot and a cold cat shot. It's a solid steel rod, 6-7 inches long, with a machined collar at either end. As the aircraft taxis onto the catapult track, the forward end of the holdback is fitted into a receptacle in the aircraft's belly. The aft end is secured to a cable from the deck. The A/C is inched forward very slowly to take up the slack in the cable. (If this is done too quickly the holdback can be stressed, and the A/C must be pushed back and a new holdback fitted. An unpopular mistake by the pilot.) As the aircraft turns up to full power, the holdback fitting is the weak link in the high-tension train that holds the A/C back. And here's the idea of the holdback: At one point the rod is machined down to a smaller diameter which gives a weak point. When the catapult fires, the force of the cat stroke breaks the holdback fitting at the weak point, and the A/C is free to be pulled down the cat track. Simple, but the Navy pays a lot for holdback fittings because the tolerances and quality control must be perfect. The tensile strength of the steel must be exact, and the tensile breaking point at the weak groove must be precisely known. The holdback fitting (which is specific to each type of aircraft) must break at the right millisecond during the pressure build-up phase of the cat's power stroke. Too soon, you may have a cold cat shot. Too late, you can tear the aircraft apart or smack the pilot silly. The aircrew's lives literally hinge on the holdback manufacturer's quality assurance program. The aft end is secured to a cable from the deck. The A/C is inched forward very slowly to take up the slack in the cable. (If this is done too quickly the holdback can be stressed, and the A/C must be pushed back and a new holdback fitted. An unpopular mistake by the pilot.) As the aircraft turns up to full power, the holdback fitting is the weak link in the high-tension train that holds the A/C back. And here's the idea of the holdback: At one point the rod is machined down to a smaller diameter which gives a weak point. When the catapult fires, the force of the cat stroke breaks the holdback fitting at the weak point, and the A/C is free to be pulled down the cat track. Simple, but the Navy pays a lot for holdback fittings because the tolerances and quality control must be perfect. The tensile strength of the steel must be exact, and the tensile breaking point at the weak groove must be precisely known. The holdback fitting (which is specific to each type of aircraft) must break at the right millisecond during the pressure build-up phase of the cat's power stroke. Too soon, you may have a cold cat shot. Too late, you can tear the aircraft apart or smack the pilot silly. The aircrew's lives literally hinge on the holdback manufacturer's quality assurance program. | ||||||||

| Hook-skip | Every Navy pilot's favorite excuse for a bolter. If the pneumatic bungee pressure (or whatever) holding the hook extended is low, the hook may bounce upon hitting the deck, and will probably not catch a wire. A worn hook point may give the same result, or, worse, may spit a wire. | ||||||||

| Hook-to- ramp |

| ||||||||

| "Huffer" (start cart) | The jet engine start cart, used on the carrier, and ashore if no fixed airhose is available. The jet engine compressor needs to turn at perhaps 20% RPM before it'll sustain ignition, and since fighters don't have starter motors (too heavy), the huffer does the job by blowing a high velocity air stream through a special fitting to turn the engine. The pilot signals with a two-finger "turn-up" sign to the plane captain to start turning the engine. | ||||||||

| "Inchop" | Or "in-chop." When a ship or a task group, such as a carrier and escorts, arrives for duty at a designated sea theater or command, it inchops the theater or command. When it leaves for home after completed duty it outchops the command. (For the really curious, the word is made up of the words "change of operational command.") | ||||||||

| Inflight engagement | No, not romance on United Airlines, but an even more hazardous adventure: On a carrier landing, the tailhook catching a wire before the wheels touch the deck. Ooh. A bad moment in store. The arresting gear slows the still flying A/C abruptly to below flying speed, and unceremoniously slams it to the deck. Usually busts the landing gear and much of the rest of the airplane, not to mention the pilot's back. How do we get into this scrape? Probably a wave-off in close (too close), scraping the deck with the hook, and the aircraft in a nose high attitude, desperately seeking succor. | ||||||||

| Integrity watch | When flight ops aboard the carrier are secured and civilized folk hit the rack for the night, an "integrity watch" crew patrols the flight deck and hangar deck to ensure safety and proper tie-down of the aircraft, which can work themselves loose in a heavy sea. Nominally in charge of the watch is the integrity watch officer (of course a chief is really in charge of the crew, as always), a job that falls mainly to the nuggets in the squadron. It's a lonely watch, wandering the decks for four hours in the middle of the night, the time ticked off by the bells each half hour; and it usually comes when you're scheduled for three hops the next day. What the hell. Sleep some other night. | ||||||||

| Island | The carrier's superstructure, rising from the Flight Deck on the starboard side. Contains the bridge, "Pri-Fly" and other mysteries. Messes up airflow on final approach. See Burble. | ||||||||

| JBD | Jet Blast Deflector. Large steel plates that pivot up out of the flight deck behind a catapult, to protect from the blast from an aircraft at full power on the cat. | ||||||||

| Kneeknocker | Busted knees are a Navy man's occupational hazard. Ship-board passageways are interrupted at regular intervals by waterproof, airproof, fireproof hatches, which supposedly will prevent the ship from sinking or going up in a conflagration. Well, the lip of the hatch is just below knee level. If you lift your legs just right you'll make it through; if you don't your knees are toast. | ||||||||

| Ladder | Onboard ship, what you would elsewhere call stairs is a ladder. A Navy man calls stairs a "ladder" even in his house. | ||||||||

| Launch | The first phase of a carrier's cyclic flight operations. (See Recovery.) At the start of the launch sequence, the A/C are parked on the aft half of the flight deck. As launch operations begin, A/C are taxied forward and directed by Yellow Shirts onto the next available catapult. Typically, a catapult stands idle for only a few seconds before the next bird is being hooked up. | ||||||||

| Leeward | The side of the ship away from the wind, or in the downwind direction. Sailors pronounce it "loo-erd". Opposite of Windward. | ||||||||

| Liberty | Shore leave for the crew when the ship is in port. For the enlisted crew this is strictly enforced as a given number of hours ashore. (For the excitement of getting ashore, see "Liberty boat," below.) For the officers, there's more leeway. (Here's a mariners' term, by the way: leeway–the space between the ship and any downwind obstruction, like a rocky coastline.) Lots more leeway; see "admin." | ||||||||

| Liberty boat | When the carrier visits a foreign port, it does not tie up to a pier. For reasons of security and operational readiness the Captain anchors outside the harbor, usually 1/2 mile to a mile offshore. But the ship has 5-6000 sailors and officers who have been promised liberty ashore. The solution is liberty boats, open inboard engine mass movers that hold 30-40+ human sardines. Operating the boats merges two factors which can lead to more excitement than you need: 1. There is often a sea state that makes the boats bob up and down several feet (which the carrier does not), so that to step from the boat's gunwale to the small platform at the bottom of the ladder hanging over the ship's side and moving up and down relative to the boat requires a sure and deft step; and 2. On the returning boats, in the black of night, most of the sailors are dead drunk! One or two (sober) sailors at the bottom of the ladder, tied with lifelines and outfitted with rescue equipment, stand ready to assist in this disaster-waiting-to-happen. If the sea state is too great, the Captain may cancel liberty, but the crew response would be near-mutinous. Also, canceling the return boats late at night if the sea picks up would leave the crew stranded ashore. There's always an officer riding and nominally in charge of the boat: the dreaded Boat officer watch! | ||||||||

| Lineup | Lining up the aircraft for landing can be tricky enough on a land-based field, if there's a crosswind. On a carrier it's a real bear! The British 1940s invention of the angled deck solved the bothersome problem of landing aircraft crashing into parked aircraft on deck, if they missed the wires. But you rarely get something for nothing, and "The Angle" brought on serious difficulties in lining up the aircraft for landing. The offset of the landing deck by 10-12 degrees from the carrier's heading brought both the difficulty of providing wind "down the Angle," and the awkward fact that the strip you're trying to land on is moving off to your right at a speed of perhaps 20-30 knots. Crabbing for both crosswind and the moving goal line, while you're working to stay on speed and glideslope is an extraordinary challenge, which doesn't get any easier in the dark of night. (To top it off there's the burble – see that.) The tendency at touchdown becomes a right-to-left drift, with the very real hazard of going over the port edge, hanging by the hook, if you've caught the 4-wire and are off centerline. | ||||||||

| LSO |

| ||||||||

| LSO code | The Landing Signal Officer (LSO) grades each landing aboard ship, using a standard set of abbreviations. The graded landing (pass) begins when the aircraft rolls into the "groove" after the turn onto "final" and the pilot makes his ball call. Some of the more common codes, from the NATOPS LSO manual, are:

So a below-average pass might look like: (OK)2 LIG HIX CDIM CIC DNAR. [For those not inclined to figure that out, it's "Fair pass to the 2 wire, long in the groove, high start, came down in the middle, climbed in close, dropped nose at ramp.] | ||||||||

| Marshal | Sometimes used as a synonym for "rendezvous," Marshal (as a noun) usually refers to the specific mid-altitude rendezvous point designated for check-in with the carrier's 'approach control' (which is called "Marshal"–as in "Allstar Marshal, Gruesome One checking in") before returning to the ship to land. It's the aircraft holding pattern, typically at about 20,000 feet, from which the carrier's radar controllers feed the aircraft into the landing pattern. "To marshal" is to show up at the marshal point. | ||||||||

| Meatball | See the Ball. | ||||||||

| Mess | While the officers' on-board eatery is known as the wardroom, the enlisted men's somewhat-less-than-4-star establishment is tellingly called the Mess. But officers have a "mess" too; a special round-the-back-of-the-galley greasy spoon for watch-standers and pilots between flights, where you are free from protocol and from the uniform of the day. You can eat in your flight suit and feel free to be as unwashed as you please. In fact you'd better look a little filthy, or you're not supposed to be there. A liberating place. (And see "midrats", below.) | ||||||||

| Midrats | "Midnight rations." When your former fighter pilot hubby rolls out of bed in the middle of the night and you hear the frig door open, that's midrats. He's just trying to duplicate how it was back in the day.... Scheduled to launch in the dark of night, he would stop by the mess (see above) for some midrats before taking off. This usually involved downing some undefinable stiff goo, mostly made with eggs, perhaps made yesterday. Made you wish you'd get shot down and captured. | ||||||||

| The Mirror | The optical landing system mounted on the port side of the flight deck, and stabilized for the roll, pitch, and yaw of the ship. The pilot keeps an amber center light ("the ball") lined up with green "datum lights" to stay on the glide slope. (This isn't easy.) It used to be an actual mirror; now a Fresnel lens is used but it's still called a mirror. | ||||||||

| Moon | Naval aviators' distaste for black-ass night carrier landings makes them all expert on the phases of the moon. The moon rises about 50 minutes later each day, and savvy carrier pilots know exactly how it will relate to their scheduled flight time. | ||||||||

| "Mother" | General radio designation for the carrier, the "mother ship". An airborne aircraft may hear: "Gruesome four, Mother advises fouled deck; your signal delta." | ||||||||

| Night Trap | Night landings are a Navy pilot's scariest moments, unless they're pinkies. | ||||||||

| "Now hear this!" | It's just like in the movies: The bosun's whistle blows in the ship's speakers, followed by this hallowed phrase, intended to induce respectful and attentive listening by the crew. If your dad's a Navy man, you've heard this phrase a hundred times at home. You can be the judge of whether it induced respectful and attentive listening. | ||||||||

| OK | A well-executed carrier landing, as graded by the LSO. The ideal "OK-3" pass catches the target No.3 wire. A pass so steady that the LSO suspects the Lord himself is at the controls rates an OK-3 [underlined]. An almost-OK pass is "(OK)" [in parentheses]. An OK-3 grade by the LSO in everyone's earshot in the Ready Room may be the greatest little high you'll have that day. Your chest comes out a bit, and that smile just suggests that you'd be willing to instruct the others, if there were only time. But for the opposite kind of pass, see "Cut." | ||||||||

| OLS | Optical Landing System. See "Mirror". | ||||||||

| Outchop | When a ship or task group leaves a sea theater or command it is said to "outchop" that theater or command. See "inchop" for the obvious flip side and for some explanation of derivation of the term. | ||||||||

| Overhead | Nope. Bad guess. Has nothing to do with cost of doing business. The overhead is precisely what you landlubbers would call a "ceiling": "Easing out the champagne cork with his thumbs, Ensign Dumbo heard a loud crack as it impacted the overhead." Of course it works as an adjective, too: "Sufferin' catfish! if the overhead light ain't burned out again!" | ||||||||

| Paddles |

| ||||||||

| Pass | Naval Aviators have been known to make various kinds of passes, but onboard ship, it means an attempt at a carrier landing. Often successful, but some pilots ...uh... like to make two or three passes (see "bolter") before making a trap. | ||||||||

| Passageway | There aren't hallways or corridors on board ship. If it looks like a hallway or corridor it's a "passageway." (To a Navy man, of course, the hallway in his house is a passageway, too.) Things you're likely to see in a passageway include hatches, bulkheads, spaces, ladders, kneeknockers, and dogs, and none of them mean whatever they sound like. | ||||||||

| Pattern | By itself this word usually refers to the daytime VFR flight pattern (landing pattern) around the ship (or the field). This is the place for the squadron to look good. The landing pattern of a carrier is a very specific four-dimensional flight path designed to get all aircraft aboard in the minimum amount of time, because the carrier is especially vulnerable during launch and recovery operations, as it has to steam at a steady course and speed and the recovering aircraft are low on fuel. The landing pattern is closely coordinated with the holding pattern A flight of four (say) approaches the carrier from abaft, passing close abeam the starboard side of the ship at 400+ knots, 800' altitude, in starboard echelon. The drill is to make the coolest sound you can as you enter the break. (Some years ago, opening the "oil cooler door" on the F-8 Crusader would give a very cool wolf-howl-like sound. Coming to idle just before reaching the ship gives an eerie silence.) Each A/C breaks hard left with a few seconds interval between each. With power at idle and speed brakes out, speed bleeds off in the 180° turn, and the A/C levels downwind off the port beam of the ship, which is headed in the opposite direction at up to 30 knots. When abeam the fantail (at the "One-eighty" position) at an altitude of 600 feet, you start your port descending turn toward the ship, which is still pulling away. About halfway through your turn, at the 90° position (the "90"), you should be on speed and at about 450'. You intentionally overshoot the ship's wake by about 10° to line up with the angle deck, roll out in the groove, acquire the ball, reduce power to establish your rate of descent (because now you're wings level and need less power for the same descent rate), and make your ball call to the LSO. Then you merely stay precisely on glideslope, speed, and centerline of the deck which is moving away and to the right at perhaps 30 knots. The pass is perfect; you go to full power on touchdown, power to idle when you're stopped. As you touch down the next A/C is at the 90° position (the "90") in the pattern, ready to roll into the groove. You're pulled backward by the arresting cable. The yellow shirt signals hook up. You raise the hook and follow his signals to move forward, fold the wings, and turn right. He passes you on to the next director who signals you to speed up. You cross the yellow foul line on the deck. A red light on the LSO platform has indicated "fouled deck" since you touched down. Now you're clear and the green "ready deck" light comes on. By this time the next A/C may be just 5 seconds from touchdown. A landing will occur every 20-some seconds during recovery. And that's the pattern. (YouTube has a reasonable demo at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BjX1Qa22AqA ) | ||||||||

| Pinky | A daylight flight that lands just after sunset, giving you credit for a night landing while you essentially still have daylight. The squadron flight officer had better be equitable with giving out pinkies, or fights are likely to develop. (There are occasional rumors that CAG, an older and wiser man than most, often has important meetings later in the evening and finds it necessary to get his quota of night traps earlier in the day, i.e., a pinky, but we think that's just malicious gossip. Wouldn't happen. Eh?) | ||||||||

| Pitching deck | This is when you really need the LSO. What am I doing flying off the carrier in a storm, anyway? Well, OK, "operational necessity"... But in spite of stabilization of the ship, the flight deck will rise and fall. And since the OLS is stabilized to the glide slope, all that pitching is hidden from the pilot. The LSO's visual call is still the best way to avoid a meeting of the aircraft with a rising deck. Even if a ramp strike does not occur, the rising deck can crush an aircraft's landing gear. | ||||||||

| Plane captain | The "PC" is usually a junior enlisted man with a great responsibility. His assignment as plane captain for a particular aircraft means he ensures that the aircraft is preflighted and ready for flight when the pilot comes to man. The PC assists the pilot in getting strapped in, and directs the start-up sequence from the deck. The PC's name is often painted on his aircraft, which is a great source of pride. | ||||||||

| Plane guard |

| ||||||||

| PLAT | "Pilot's Landing Aid Television." (Or something like that.) A typical Navy acronym for a very scary "Pilot's Landing Aid." The camera for this demonic device is buried in the flight deck, looking up the glide slope. Each landing on the ship is televised live in the Ready Room. How motivational is this? I've watched several aircraft go up in flames on the PLAT before going out flying. | ||||||||

| Poopy Suit | Or "bag." It's not what it sounds like, whatever that is. Formally an "Antiexposure suit", exposing yourself in this contraption would be damn near impossible. Relieving yourself is equally impossible. Plan an extra ten minutes in the Ready Room to get this monstrosity on. This rubber coverall fits, more or less, over the standard flight suit, and is required flying gear over water whenever the air-and-water temperature goes below what the chart says. Without it, should you go in the drink, you'd be flounder-food in a hurry. In temperate climates the "bag" will normally be worn throughout the winter months on carrier-based flights. | ||||||||

| Port | Now let's learn this once for all: Port is LEFT. Starboard is the other way. Because the steering oar was on the right in old (viking age) ships, they docked the ship with the left side to the pier–or port. So that was the "port" side of the ship. | ||||||||

| Pri-fly | "Primary Flight Control." This is the carrier's 'control tower'. The domain of the Air Boss, the god of the flight traffic pattern. Pri-fly is also staffed with experienced pilots who can advise on emergency procedures if needed. | ||||||||

| Ramp | This is the part of the carrier you hit and kill yourself on if you're low on landing. | ||||||||

| Ramp strike |

| ||||||||

| Ready room | A spartan room on the carrier (or in the hangar, when ashore) where the pilots spend much of their time yabbering. Contains a desk for the SDO (Squadron Duty Officer), a black-and-white TV set (the PLAT) that shows all landings from a camera buried in the flight deck, and a reclinable chair for each squadron officer, to do with as he likes. Flight briefs and debriefs, personality clashes, and games of Ace-deuce take place here daily. | ||||||||

| Recognition | An entertaining slide show-slash-quiz which the AIO puts on from time to time in the Ready Room. It consists mostly of endless dozens of slides with fuzzy black-and-white photos of "enemy" ships. You're supposed to learn to tell them apart, so you can report back in the flight debrief. (But it's a generic trait among pilots that they don't care about ships. They recognize three kinds: Flat-tops, subs, and "others." The AIO eventually just gives them a camera.) The second best part of the show is that the AIO turns off the lights in the Ready Room so you can sleep. The best part is that your squadron mates' howls will wake you up when the spicy shots come up on the screen. No matter how long the ship has been at sea, the guys have no recognition problem with these uh ... hulls. An AIO who fails to spice up his Rec. show would be shunned, since he has no other known redeeming social value. | ||||||||

| Recovery | A carrier's cyclic flight operations is separated into launch and recovery (landing) phases. During the recovery phase the flight deck starts clear of aircraft. Upon landing, each A/C is taxied forward and parked clear of the landing area. An aircraft will land every 20-some seconds during the recovery phase.

| ||||||||

| Red Ball | When the pilot is low on the glide slope, the ball turns red. Red like blood. Better do something about it. Like add power. Lots of power. Now! | ||||||||

| Romeo Corpen | means the ship's heading during underway replenishment ("unrep"–you're now one of very few who know this; go out and impress someone). See the analogous "Fox Corpen." | ||||||||

| Rounddown | The Ramp, Fantail, the hurtin' zone of the carrier deck. But if you don't hit IT, it won't hurt YOU. | ||||||||

| Sand Crabs | Usually plural. Civilian so-called workers who are contracted to do repair work on the ship, often in a foreign port. In most countries they're laggards. In Japan they're real workers. | ||||||||

| Shooter | Slang for the Catapult Officer. | ||||||||

| Space | More often "spaces." Any or all rooms or areas on board ship, in or around a hangar, etc. Each room or segment of a passageway or deck has a space number. "The Chief will inspect the Avionics spaces at 0800." A Navy dad will naturally say, "Not until you've cleaned your space, Billy." (That would be Billy's room.) | ||||||||

| Spaghetti | The "wires", the arresting gear in the landing area on a carrier. You're supposed to land in the spaghetti. | ||||||||

| Spit a wire | The steel point of the tailhook works in a violent environment, and needs frequent replacement. If it becomes worn, the hook may initially catch a wire, but fail to hold it when the pressure builds as the aircraft decelerates. If the hook "spits" or releases the cable at this point, the aircraft will probably not regain flying speed and will likely end up going in the drink. A serious, sometimes fatal, consequence of overlooking a small part. | ||||||||

| Spotting the deck | A nasty habit. Like in baseball, taking your eye off the ball is a bad idea in carrier landings. "Spotting the deck", or switching your attention to the deck for even the last second before touchdown will usually result in an increased sink rate and often a three-point landing and overstressed landing gear. LSO's uniformly condemn the practice, but nevertheless it thrives. Especially after a couple of bolters when it's "Get aboard or bingo." All this said, many experienced Naval Aviators routinely spot the deck, using the dip method to get aboard, often safely. | ||||||||

| Stabilization | More or less successful efforts to fool Mother Nature. The carrier is stabilized to reduce pitch and roll movements. The result may be unpredictable figure-8-like movements of the ramp. The mirror is stabilized to the glide slope. The result is a ramp that can rise without the pilot having any clue. The aircraft is also stabilized in pitch and yaw (e.g., "yaw stab"), by electronic systems that can and do go out of control. You can't fool Mother Nature. | ||||||||

| Starboard | The Right side of the ship or whatever. Dates from the viking ships, where the steering oar was mounted on the right ("steerboard"–or "styrbord" in vikingese) side. And see "Port", if you feel like it. | ||||||||

| Stash | A theoretical term for booze illegally stashed in pilots' staterooms. This would be a violation of Navy Regulations, and therefore is thought by some to not actually happen. | ||||||||

| Stateroom | Senior pilots get their own room, but don't have any fun. Junior pilots share a stateroom, and that's where the parties are, such parties as you can have with a bunch of sleepless zombies. | ||||||||

| Steam | The U.S. Navy is not known to operate steam vessels any longer, but still the ships all "steam" when they're underway. [No sooner do I make this fine ironic point than Dave "Fireball" Johnson points out that nuclear ships run by steam(!)–correct, of course, but I ask you, is a nuke a steam ship?] Navy ships at sea spend a fair amount of time just ... being, but like sharks they have to keep moving so what's there to do but ... steam? | ||||||||

| Tailhook | Or just "Hook". What distinguishes a naval aircraft. A steel hook lowered hydraulically or pneumatically from the rear of the aircraft, intended to engage a cable of the carrier's arresting gear to bring the aircraft to a quick stop. Attaches to the aircraft via a flexible fitting required to take the full force of bringing a 25 ton aircraft from 150+ mph to zero in about 2 seconds. Its engineering is one of the marvels of modern technology. | ||||||||

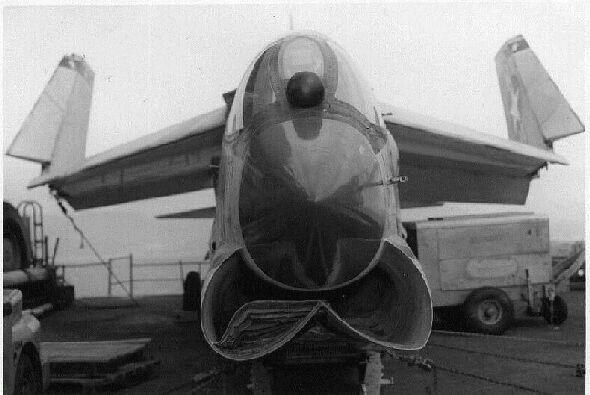

| Three-point landing |  Ouch! A Navy jet is built to land on its two main mounts. After touchdown the hook catches a wire and slams the nose gear down. But landing on the three mounts together is a bad deal; it may well collapse the nose gear. You get into this predicament when you're high on the glide slope. Seeing the meatball climb on the mirror you try to correct down with a poorly executed dip. Your nose gets low, your sink rate's high, and before you're reestablished you hit the deck with all three mounts. If you're lucky, the hook will catch a wire, and though the nose gear may collapse, as on the grim-looking Crusader at right, at least you're aboard. If you're less lucky, with the hook farther from the deck than in the normal landing attitude the hook may skip, the A/C may bounce, and you're back in the air with a busted nose gear. You's in big trouble, boy. Ouch! A Navy jet is built to land on its two main mounts. After touchdown the hook catches a wire and slams the nose gear down. But landing on the three mounts together is a bad deal; it may well collapse the nose gear. You get into this predicament when you're high on the glide slope. Seeing the meatball climb on the mirror you try to correct down with a poorly executed dip. Your nose gets low, your sink rate's high, and before you're reestablished you hit the deck with all three mounts. If you're lucky, the hook will catch a wire, and though the nose gear may collapse, as on the grim-looking Crusader at right, at least you're aboard. If you're less lucky, with the hook farther from the deck than in the normal landing attitude the hook may skip, the A/C may bounce, and you're back in the air with a busted nose gear. You's in big trouble, boy. | ||||||||

| Tilly | A wheeled crane used on the flight deck. Painted yellow, like all moveable (nonflying) flight deck equipment, the tilly is compact but powerful, able to clear disabled aircraft or parts thereof from the landing area in a hurry. | ||||||||

| Tin can | A naval aviator's fond nickname for a destroyer (ship). Tin cans have served as seaborne forward air controllers in a battle environment, providing navigation and other info to airborne aircraft. | ||||||||

| Topside | You just can't say "upstairs" onboard a ship. It's Topside. Navy folks use this term ashore, too. (You can't say "downstairs", either. And of course there aren't "stairs" onboard ship.) | ||||||||

| A Trap | An arrested landing. Navy pilots practice carrier landing techniques constantly when ashore. See MLP. | ||||||||

| Unrep | Underway Replenishment. A carrier can stay at sea for months at a time, but needs a steady supply of groceries, razor blades and toilet paper. And one or two other things, like fuel if it's oil burning, and jet fuel in any case. While some high priority items may be delivered by COD, most supplies come aboard from a cargo ship or oiler which rendezvous'es (?) with the carrier at sea. The at-sea resupply "evolution" (the Unrep) can be more exciting than you really want when the high seas are really high (sea state of 5 is the max for Unrep), as the two ships are steaming side by side, connected by one or more high lines or fuel hoses, with about 160 feet of separation. (As a bonus factoid for trivia buffs, the Unrep heading is known as the "Romeo Corpen.") | ||||||||

| Wardroom | The officers' dining room onboard. Chipped beef is a real favorite. And coffee made with water that tastes of jet fuel. (The ship makes its unique "fresh" water from the polluted salt water it's steaming through. It also disposes of its wastes in the same waters. During "cyclic ops" the ship steams back and forth in the same sea lane, dumping waste and making drinking water.) You're expected to behave in the wardroom, a challenge for most aviators. (But if you're in-between flights in a sweaty flight suit you can go to the dirty-shirt mess and not have to behave at all.) You're not supposed to talk about politics, sex, or religion in the wardroom. It often gets very quiet there. | ||||||||

| Watch | A period, usually 4 hours, when the young fighter pilot is actually asked to do something other than eat, sleep, swear, fart, and fly. All young fighter pilots take offense at being told to stand a watch; it seems an inexcusable waste of their immeasurable talents. Onboard ship their least favorite watches are the Boat Officer Watch, the Integrity Watch, and the all-day Squadron Duty Officer (SDO) watch, also known by the Stalinesque-sounding appellation ""The Duty"". [Now here's a scoop–the logic is complex, but try to follow it: The Navy needs Landing Signal Officers (LSO's) to keep their pilots alive. LSO's regularly stand an often miserable and always hazardous watch on the LSO platform, out in the weather and practically under the wingtip of landing aircraft. Now, no one in their right mind would volunteer for that. (Let's dismiss the puling claim that no one in their right mind flies jets off boats...) Except that the LSO is a hero among his peers. He has powers–seemingly magical–and for many he's the reason they're still alive. And if there's one thing more precious than life itself to a fighter pilot, it's getting the respect of his peers. (Are you with me so far?) Ergo, an LSO doesn't have to stand any other watches, like the great unwashed masses of young aviators do. So, the bottom line is: A J.O. is motivated to get out of these crappy watches that waste his exceptional talents by becoming an LSO and getting peer respect! And that's why these watches exist. (You read it here first!) All this was figured out decades ago by the brass, and I take back everything I've said about them. They're obviously brilliant.] | ||||||||

| Wave | Traditional term for what the LSO (Landing Signal Officer) does. As in "Who's waving this recovery?" The LSO doesn't usually wave his arms any longer, but used to be he waved a pair of paddles to indicate glide slope and lineup information to the pilot on final approach to the carrier. The paddles were obviated by development of the landing mirror, but LSOs still need to learn to work the paddles, in case the mirror goes down. And pilots need to learn to fly by the paddles–being literally waved aboard. This skill is not sufficiently practiced nowadays, so losing the mirror is now an emergency condition. | ||||||||

| Wave-off | An aborted carrier pass, where the pilot adds power and climbs back in the landing pattern. A hazardous condition may have developed–such as the deck pitching up, or the deck was fouled, or the pilot's pass was unsafe. Usually the command to wave off a pass is issued by the LSO, but the pilot can make his own choice to wave it off. | ||||||||

| Wind | The aircraft carrier likes to have close to 30 knots of wind down the deck for aircraft launch and landings. If there's natural wind, the Captain heads the carrier into the wind to launch. For landings, you want the wind to come down the angle deck, 10-12° off the ship's axis, to reduce the need to crab on final approach. So for landings, the Captain will head the ship a few degrees to starboard of the natural wind. If there's no natural wind, the Captain makes wind. (It's not what it sounds like.) He does this by steaming at 25-30 knots; but in this case the wind relative to the carrier will come down the axis of the ship, giving the pilots a starboard cross wind on final approach and bringing the burble into the groove. | ||||||||

| Windward | The side of the ship closest to the wind, or in the upwind direction. If you're planning to relieve yourself over the rail, select the leeward side instead. | ||||||||

| Wire | "The Wires" is the set of 4 heavy wound steel cables comprising the Arresting Gear. They're numbered from 1 (furthest aft) to 4. On the ideal landing the hook snags the 3-wire. Miss all 4 and you bolter. Each wire has a personality. The 1-wire: You don't want to catch this. The LSO's unhappy and you may get a cut pass. You're too low at the ramp and putting the aircraft in danger. The 2-wire: This isn't necessarily bad [the LSO may mark it "(OK)" in his book]. It just isn't perfect. You'd like a little more ramp clearance. The 3-wire: This is the target wire. Your hook-to-ramp clearance is normative. An "OK-3" grade from the LSO is the goal. If you're "on rails" down the glide slope to an OK-3, your grade is underlined and you gain stature in the Ready Room. A 4-wire is usually safe, though you're high on the glide slope. But if your glide slope is leveling in close, or you have a right-to-left drift, you may get an inflight engagement, or wind up at or over the port side scupper of the flight deck, hanging by the hook (more a problem on older, smaller carriers), or worse. "Fly-by-wire" is something else altogether. | ||||||||

| Yellow Shirt | The enlisted flight deck directors who have control of movement of A/C on the flight deck. A pilot does not move his aircraft, or any external component of his aircraft, without a positive direction from a Yellowshirt. The Yellowshirts of course wear yellow shirts. There are also White, Green, Purple, Red, and a couple of other color shirts on the flight deck, designating specific roles. (Green = maintenance, Purple = fuelers, etc.) These guys work in an indescribably hazardous environment, and deserve a lot of the medals the pilots get. |

| Go to Top of Page |

Aircraft & Flying

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

| AA / AAA | Or "Triple-A". Neither an auto club nor a 12-step program, but Anti-aircraft artillery. See also "Ack-ack" below, and Flak. | ||||||

| A/B | Afterburner. | ||||||

| A/C | 1. Aircraft. An aircraft may be called an airplane, but never a "plane". 2. Air conditioning and pressurization system. 3. Anti-collision light. 'Blinker.' (Blinking red light.) | ||||||

| Ack-ack | Anti-aircraft artillery (AA, AAA, "triple-A," flak). An unfriendly reception when going downtown. The term comes from a slang phonetic alphabet used on the western front in WWI, that began: Ack, Beer, Charlie... | ||||||

| ACM | Air Combat Maneuvering. Informally "Tactics". The traditional essence of fighter pilot training. | ||||||

| Acute | In formation flying, if a wingman is forward of his proper position in the formation, he's "acute." (Those who paid attention in Geometry might object that in this case the angle he makes with the flight is more obtuse, i.e., less acute. I say don't worry about it.) If he's too far back (more acute angle) he's "sucked." Don't laugh; these are the actual professional terms! | ||||||

| ADF | "Automatic Direction Finding," an obsolete piece of VHF radio direction finding equipment. The needle points toward whatever station you've dialed in. When you pass above it, the needle goes nuts. Big deal. You turn up the volume and the Morse code dits'n'dahs are supposed to tell you what station you've got, if you actually remember your dits'n'dahs. Which you probably don't. | ||||||

| Afterburner | (Also A/B, Burner, Blower, Heater, and (Brit) Re-heat.) The go-fast mechanism that makes fighter planes unique. The 20 feet of flame shooting out the back on a night take-off. Simple in concept, but tricky in design and execution, the idea of burning hot air and fuel in a jet exhaust made supersonic flight possible. The afterburner is basically an extension of the jet engine exhaust pipe. You "simply" spray fuel into the hot exhaust gas (while providing back-pressure protection for the engine) and you get yourself a mess of thrust. You can get twice the power of the basic engine, but you'll use 3 times the fuel. In a tactical environment the 'burner will be selected for short bursts of acceleration or climbing power, because fuel management is always critical. If you run out of fuel, you may as well have been shot down. (Of course you'll use the burner as needed in a dogfight. If you're shot down, you might as well have run out of fuel.) | ||||||

| Aileron | These ingenious flight control surfaces on the trailing edge of the wing were invented by birds. (Don't write me about pterosaurs being first–they flexed the whole wing to bank, though the principle is the same.) When a soaring bird wants to turn left, it lowers the trailing flight feathers on the right wing, which increases the lift on that wing and raises it relative to the left wing. At the same time, the bird raises trailing feathers on the left wing, which spoils the lift there and lowers the left wing. These two coordinated movements are exactly copied by an aircraft's ailerons when the pilot moves the stick to the left, thereby putting the aircraft in a left bank, resulting in a left turn. (This is not going to be a lecture on aerodynamics, but the only effective way to turn an aircraft is to bank it. Because the lift vector generated by the wings is always perpendicular to the plane of the wings–i.e., straight up when you're level–when you bank left the vector points up and left. The left-pointing vector component drives the aircraft–or the bird– to the left.) | ||||||

| Airway | The air equivalent of roads and sea lanes. Airways are defined by TACAN fixes (radials and distances), and keep commercial traffic organized. Anyone (including military aircraft) flying above 18,000 feet in the U.S. flies under air traffic control by FAA, and is normally on an airway. High altitude (jet) airways are designated with a "Juliet," as J-22, while low altitude airways are designated with a "Victor," as V-20. Aircraft fly at an assigned altitude, and you can check your airline pilot with this hint: Eastbound traffic (above 18,000 feet) fly at odd thousands plus 500 feet (say 27,500'), while westbound planes fly at even thousands plus 500 (say 28,500'). So there's 1000 feet of vertical distance between planes in opposite directions. (See "Flight Level" for a fine point about altitudes.) | ||||||