Are three gods better than one?

May 2009

More than fifty thousand years ago, my ancestors and yours (our great...grandparents were all black Africans, by the way; whoever you are, your DNA contains 99.999% African genes) spread out from east Africa to populate the Earth, doing battle along the way against our relatives Homo erectus (like "Peking man" and "Java man") in Asia and Neanderthals in Europe and the near East. As they migrated slowly over a period of tens of thousands of years, they brought with them their supply of portable tribal gods, supplementing these with new gods as needed along the way. New experiences with floods, earthquakes, drought, and other disasters required suitable gods, and these were added as new issues were encountered. For each god, rituals would be developed for influencing the god, and a myth would be created by the tribal shaman to support the need for the ritual. Eventually, quite a number of gods were recognized by the average tribe, and they all needed attention in order to avert disasters. Gradually, a hierarchy of gods was conceived by many tribes, where one of the gods would gain prominence.Abstract:

An illogical and ancient bit of Christian doctrine has had the Abrahamic religions at each other's throats for nearly two thousand years. The doctrine doesn't make sense and never made sense. So why not grow up and drop it, striking a blow for ecumenism and peace in the process?

About five thousand years ago, the first cities were being built in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq, a place that should be sacred to us for its immense contribution to our own past), and each city enjoyed its own chief god. While most cities also had additional gods, one god would be the city's protector and was particularly feted in rites and sacrifices. In one such city, says legend, lived a young boy, Abraham (or Abram), whose father was a potter, specializing as a maker and seller of idols. According to a Hebrew midrash (rabbinical exposition) on Abraham, one day when his father was out of the shop Abraham took a stick and smashed all the idols in his father's shop, except the largest one, in whose arms he then placed the stick. When his father returned and saw the destruction, Abraham, wanting to demonstrate to his father that there was only one true God, told him that the largest idol had killed all the others. His angry father drove Abraham out of his house, and Abraham became, according to Hebrew legend, the prototype monotheist.

Today, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity all trace their beginnings to the legend of Abraham and his monotheism; these religions are known as "Abrahamic" faiths. During the thousands of years prior to the last millennium BC (BCE), oral folk tales of the near-eastern and mid-eastern tribes grew and were retold and amended thousands of times: Tales of wanderings, of tribulations, of wars, of victories and defeats, of successes and failures. During the period of 900-400 BC, when the art of writing became available, scribes and priests of the Israelite tribes wrote down some of their ancient oral epic tales in the body of work we now know as the Torah, the Pentateuch, or the five "books of Moses" (Genesis through Deuteronomy) in the "Old Testament". These stories tell of the ancient Israelite (and pre-Israelite) heroes and antiheroes, such as Adam & Eve, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Moses, and Joshua, and of their struggles with their tribal god, Yahweh (Jehovah). What distinguished the Israelites and kept them together, was their adherence to Abraham's concept of monotheism, apparently mostly out of fear of retribution by the routinely angry, jealous, bloodthirsty, and vengeful Yahweh.

And both Judaism and Islam have remained fiercely monotheistic to this day. But it will perhaps come as a shock to many Christians to learn that it's only within the Western Christian tradition that Christianity is regarded as a monotheistic religion. The rest of the world sees Christianity as polytheistic, worshipping not one, but three gods. (Trying to explain the "Holy Trinity" to them doesn't help.) The polytheism of Christianity – the heresy of the Trinity – was one of the chief motivations for Mohammed to form the sect of Islam, the religion of the one true God. The doctrine of the Trinity has throughout history been the main stumbling block against reconciliation of Christians with Jews and Muslims. So while in the West today, the idea of polytheism is typically treated condescendingly as something quaint, practiced by primitive tribes long ago, those quaint primitives are really ourselves. "We have met the enemy," as Pogo said, "and they are us!" Well, let's not stew over it. This just means we're among the polytheistic majority in the world; it's just the Jews and Muslims who are the one-god oddballs.

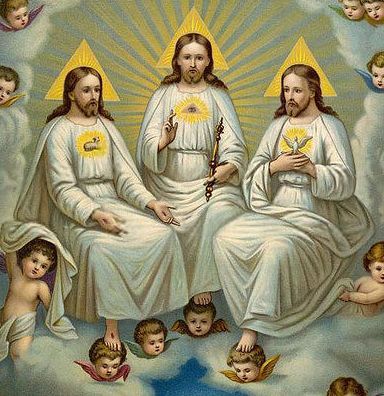

So how is it that Christians, who really aren't monotheists, think that they are? What theological sleight-of-mind has been practiced en masse upon the Christian faithful to sell them this silly and impossible doctrine of the Trinity? The doctrine is admittedly creative: it teaches that God is one God who exists as three "persons" (God the Father, God the Son – Jesus Christ, and God the Holy Spirit), a kind of troika. Not just three apparitions, but three actual persons, not bodily but "consubstantial", a word created by theologians who had never experienced anything "consubstantial". So the three persons are a unified one God, yet are distinct. Hard to grasp? Fear not: we find that investigation of the meaning of this doctrine strands on the word mystery. The Trinity, like a number of other Christian doctrines, is a "mystery", we are told by the priests, and it is not given us to understand. Well, this explanation is clear enough as far as it goes; it means that we can't understand it, and no more can the priests, bishops, and popes understand it. Which, we are told, ought not prevent us from believing in it, illogical as it is. If we then, accepting that it's a mystery and that it's not understandable, ask why we should nevertheless believe in it, we get onto more fruitful ground, because here we have historical record.

The doctrine of the Trinity was established by a church council called by Emperor Constantine at Nicaea, Turkey, in the year 325. The council was called mainly to debate and correct the "heresy" being taught by Arius, a priest of Alexandria, and his followers, who interpreted such Bible verses as John 3:16 ("For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.") as meaning that Jesus, the "Son of God", was – as it says – "begotten" (born or created) of God. That is, Jesus was neither eternal nor one with God, but had a beginning when God begot him. Further, the Arians taught, the "Spirit of God" was precisely what the Bible seemed to say: God's spirit, dispensed by God to inspire his disciples and believers. Thus, said Arius, there's one God: God the Father, while his son was his emissary sent to Earth to do God's work and his spirit imbued and motivated his believers. A reasonable and thoroughly monotheistic interpretation, which was in fact quite commonly held at the time. Nevertheless, the bishops at Nicaea made a decision more political than biblical to condemn Arius and his teaching, launching Christianity on the three-gods-in-one-god path.

The doctrine of the Trinity was established by a church council called by Emperor Constantine at Nicaea, Turkey, in the year 325. The council was called mainly to debate and correct the "heresy" being taught by Arius, a priest of Alexandria, and his followers, who interpreted such Bible verses as John 3:16 ("For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.") as meaning that Jesus, the "Son of God", was – as it says – "begotten" (born or created) of God. That is, Jesus was neither eternal nor one with God, but had a beginning when God begot him. Further, the Arians taught, the "Spirit of God" was precisely what the Bible seemed to say: God's spirit, dispensed by God to inspire his disciples and believers. Thus, said Arius, there's one God: God the Father, while his son was his emissary sent to Earth to do God's work and his spirit imbued and motivated his believers. A reasonable and thoroughly monotheistic interpretation, which was in fact quite commonly held at the time. Nevertheless, the bishops at Nicaea made a decision more political than biblical to condemn Arius and his teaching, launching Christianity on the three-gods-in-one-god path.

While the three main branches of Christianity – Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and (most) Protestants – continue to struggle with the mental gymnastics required in order to cling to the unexplainable, pre-mediaeval, "mystery" of the Nicene 3-in-1 God, a number of Protestant offshoots, such as Seventh-day Adventists, Mormons, Pentecostals, and Unitarians, have given up on it. And it's well-past time for the mainstream to kiss this disastrous, illogical, non-biblical doctrine good-bye. We can't assert that Mohammed would not have founded Islam if the doctrine of the Trinity had not been approved at Nicaea, but we can say that the evident polytheism of Christianity – as he saw it – was a spur to Mohammed's return to the "one true God" by his creation of Islam. In a world where ecumenical understanding is needed more than ever, Christianity would do well to acknowledge that the decision at Nicaea was a regrettable error, now 1700 years old, and return to the worship of a single God. Indeed, isn't the God of Genesis (El'oah, singular of El'ohim) the same God as Mohammed's Al'ah? Of course it is, as the Koran acknowledges. If reason prevails in Rome, Canterbury, Istanbul, Geneva and other doctrinal centers of Christianity, the Pope may one day visit the Muslim world as a friend, not – as he has – as an enemy.

| BRJ Front Page | See all Essays | Send a Comment |